Hopes for rural prosperity clash with concerns over deficit and hyperinflation.

A decade ago, Ian Funtalba moved to Manila to study geology, a degree not offered by universities in his home region of Bicol. Since then, he has stayed in the Philippine capital to build a career at a Canadian mining company.

"There are more opportunities in Metro Manila because the businesses are here," the 26-year-old said. He has no plans to move back, and it is easy to see why.

Bicol, an agricultural region at the southeastern tip of the main island of Luzon, is the second poorest part of the country. Its gross domestic product per capita in 2017 came to 53,000 pesos ($997), surpassing only the 30,000 pesos of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, a conflict-ridden area where Islamic State-linked militants laid siege last year.

Metro Manila had the biggest per capita GDP, at 466,000 pesos, while Bicol's neighboring industrial region of Calabarzon posted 158,000.

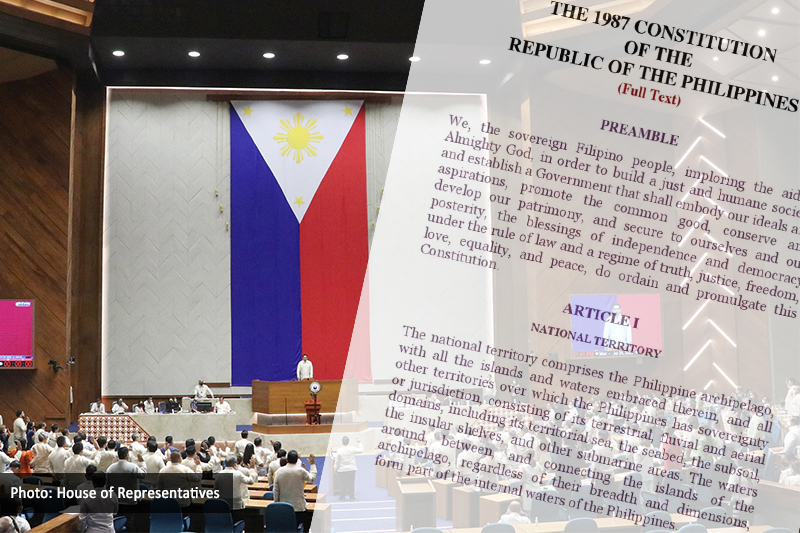

A pledge to fix that glaring disparity helped catapult Rodrigo Duterte, the former mayor of Davao in Mindanao, to the presidency two years ago. The solution, Duterte believes, is to change the constitution and replace the current unitary system with a federal one, granting local governments greater powers.

Duterte is charging ahead despite opposition and calls for caution. In his yearly national address to congress on July 23, the president sought support for what is likely to be the biggest reform of his six-year term.

"I am confident that the Filipino people will stand behind us as we introduce this new fundamental law that will not only strengthen our democratic institutions, but will also create an environment where every Filipino -- regardless of social status, religion or ideology -- will have an equal opportunity to grow and create a future that he or she can proudly bequeath to the succeeding generations," Duterte said.

In early July, a "consultative committee" dominated by lawyers and academics finished a draft charter that spells out Duterte's vision for spreading the wealth.

"What is wrong with our unitary government? It is the overconcentration of power in the national government," former Chief Justice Reynato Puno, who chairs the committee, told his 21 colleagues on July 3 as he voted to approve the draft. "We cannot continue to be a failing democracy."

Key amendments include giving 18 federated regions an equal share of the national revenue and necessary powers to build their own regional economies.

The regions "shall be given a share of not less than 50% of all the collected income taxes, excise taxes, value-added tax, and customs duties, which shall be equally divided among them and automatically released," states Section 4 of Article 3, one of the game-changing provisions.

Currently, local governments get 40% of national revenues, which are to be allocated to 80 provinces and distributed down to over 40,000 villages. Generally, places with larger populations and land area receive bigger slices of the pie.

Under the proposed charter, the impoverished Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, or ARMM, would get the same allocation as the commercial center of Metro Manila, where conglomerates like SM Investments and Ayala Corp. are based, or Calabarzon, home to numerous industrial parks. This would be on top of the local taxes each region generates.

The charter would give the regions exclusive powers over development planning, creation of revenue sources, investment and economic zones, among other matters. Businesses would be able to deal directly with a regional government, headed by a governor, unless an investment was national in scope.

The national government, meanwhile, would retain exclusive powers over defense, foreign affairs, international trade, tariffs, monetary policy, competition regulation and so on. Responsibility for labor, education and some other affairs would be shared.

Mining companies, often caught between conflicting national and local policies, may have an easier time avoiding losses. In 2015, Anglo-Swiss miner Glencore exited a $5.9 billion copper and gold project in Mindanao -- then billed as the country's biggest foreign direct investment project -- after pouring in $350 million, due to opposition from communities in the area.

Last year, three mining provinces blocked the formal appointment of Gina Lopez, a former activist, as environment secretary. She had closed dozens of mines in an interim role.

If the new charter accelerates regional development, it could help lure back the millions of professionals who have taken jobs in congested Manila. Still, many are wary of the potential consequences -- even top members of Duterte's economic team.

Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez told senators on Aug. 7 that the draft is vague about revenue and spending. "Who is going to pay for the national debt, for the military?" he asked. "I mean, if it needs additional capital, who is going to put it up?"

The 50-50 sharing, Dominguez said, could cause the budget deficit to balloon and send interest rates "to hell."

"If we don't manage this correctly, this can end up [being] a fiscal nightmare."

Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Ernesto Pernia last month said the expensive shift to federalism could put the country's investment-grade credit rating at risk. "That's really going to wreak havoc in terms of our fiscal situation," Pernia told One News, a local TV station.

Emboldened by the warnings of Duterte's own economic managers, business groups have started to speak out. In a joint statement on Sunday, the groups said they "echo the concerns" about "ambiguous provisions on the division of revenue and expenditure responsibilities."

"We worry about the dire consequences that such fiscal imbalance could have on the economy and the Build, Build, Build [infrastructure] program," they added.

Consultative committee member Fr. Ranhilio Aquino, dean of the San Beda Graduate School of Law, was clearly irked by the pushback from Dominguez and Pernia and called on Duterte to fire them. But economic experts back the secretaries' cautious assessments.

"If we don't manage this correctly, this can end up [being] a fiscal nightmare"

Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez

Rosario Manasan, a senior fellow at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, a state think tank, said instituting a federal government would cost an additional 55 billion pesos or so a year. "It will have to come from the pockets of taxpayers," Manasan told a senate hearing last month.

Bernardo Villegas, an economist and one of the framers of the current constitution, warned of hyperinflation. "Imagine," he said, "the duplication of all expenses of all levels and the completely arbitrary way of putting together provinces for the so-called federal states."

Individual businesses, loath to provoke a president who has pressured tycoons, typically decline to comment on what they call a "political issue." But executives who dare to talk sound less than enthusiastic.

Even without a charter change, local governments already have a say in how business is conducted, noted Manuel Pangilinan, who chairs telecom company PLDT, Philex Mining and Metro Pacific Investments, which holds a range of infrastructure interests.

"The local government units are involved in approvals, so ... maybe you dress the puppet in a different form," Pangilinan said.

In any case, the economic reforms are entwined with political reforms that also face resistance.

Under the new charter, the president and vice president would be elected jointly, much like in the U.S. Other changes cut into vested interests, such as a ban on political dynasties.

This is likely to face opposition in a congress where 70% of members belong to powerful political clans, as shown in a 2016 study led by scholars from Ateneo de Manila University.

In some provinces in Mindanao, over 50% of positions are occupied by dynastic clans, according to Ronald Mendoza, dean of the Ateneo School of Government. The study also found that areas ruled by dynasties are among the poorest.

Proponents of the ban stress that without it, the federal system would only perpetuate clan dominance.

Yet Duterte may need a more compelling case. In a Pulse Asia survey in June, only 18% of the respondents said the constitution needs to be revised. Thirty-seven percent rejected the change, while 30% saw no need to amend the document now and the rest were not familiar with the issue.

Duterte, the first president to hail from Mindanao, aims to tap into a bitter sentiment common in the countryside: that Manila exploits rural areas.

"For as long as I can remember, the bulk of the income generated in Mindanao used to be remitted to what we, in Mindanao, refer to as the 'Imperial Manila,'" the president said in his July 23 speech. The money, he said, is used "to fund national projects primarily in the Metro Manila area," leaving places like Mindanao with a "pittance."

"Mindanao was dubbed as 'The Land of Promise,' and Mindanaoans say in derision that this is so because what it got from the government through the years were promises, promises and more promises."

The prospects for moving the charter through both legislative chambers are unclear. The House of Representatives, controlled by Duterte allies, wants to tackle it soon. But Sen. Panfilo Lacson said the document is waiting to be "cremated" in the Senate.

Past administrations also tried to change the constitution, crafted in 1987 after the fall of strongman Ferdinand Marcos. Marcos had amended the previous charter to prolong his term, and fears of a repeat hampered his successors' attempts. Duterte, though, has said he is prepared to step down once a federal government is in place.

The president is rolling the dice amid declining but still solid public support. Though his popularity has taken a hit from stubbornly high inflation, a Social Weather Stations survey conducted in June showed 65% of Filipinos are still satisfied with him.

Now the question is whether Duterte can persuade enough politicians and ordinary Filipinos to embrace his dream of altering the country's bedrock document -- and whether the government can avoid that fiscal nightmare scenario.

Nikkei staff writer Mikhail Flores contributed to this report.